An Intimate Look at Intimates: The Feminist History of Underwear

By Madelaine Millar

Photographed by Kasey Arko

This article has been adapted for the web from our Intimacy Issue.

Underwear is a topic that is literally near and dear to many of our hearts, and one we may think we understand fully. However, underwear is more complex than cotton and spandex. The history of lingerie is tied closely to the history of American feminism and women’s social and sexual liberation.

For most of history, rich women wore corsets and petticoats while poor women didn’t bother with undergarments. Although there were slight stylistic shifts over the centuries, there were no major changes in how women wore underwear until the late 1840s and early 1850s. It was then that early feminists such as Elizabeth Smith Miller, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer, after whom the style would later be named, began wearing shorter, knee-length skirts and baggy, ankle-length pants instead of layers of petticoats. This let them walk, run and even ride bicycles without difficulty. Many of these women, most notably Elizabeth Cady Stanton, used their newfound physical and social mobility to organize the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, which is widely recognized as the beginning of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

In the 1910s, women began to cast off the corset in favor of the more comfortable and flexible brassiere, a term first coined by Vogue in 1907. Although the first patents for bra-like devices can be traced back to 1859, the first widely popular bra was invented out of necessity in 1910 by Mary Phelps Jacob. Nineteen years old and on her way to a debutante ball, she found that her corset didn’t sit neatly under her slinky evening dress, so she fashioned the first backless bra out of two handkerchiefs, some cord, and a pink ribbon. After receiving compliments on her graceful mobility all night, she decided to pursue a patent, which was granted in 1914. With a better option available and a pressing need for the metal from corsets to support the war effort, bras took off in the 1910s and gave women more freedom to move than ever before. The shift also saved enough metal to build two full WW1 battleships. In 1920, women gained the vote and while that victory that can’t be attributed solely to bras, it was certainly made easier by the freedom of movement they afforded.

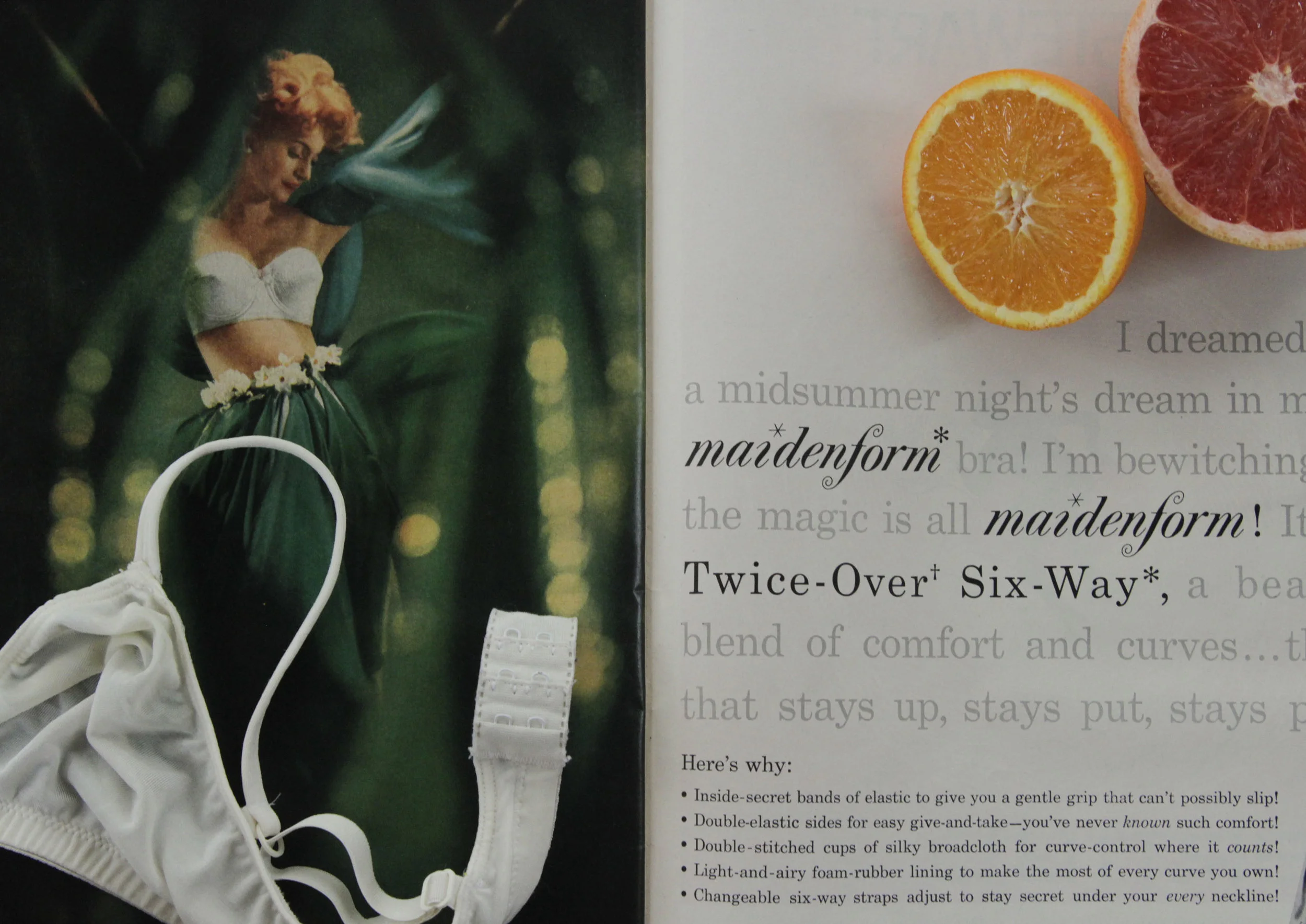

The prevailing trend in the 1940s and 1950s—pronounced and even pointed breasts, made fashionable by actresses like Lana Turner, Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe—was a dramatic departure from the boyish look of earlier decades. Bra technology was advancing, bringing the advent of cup sizes, bullet bras, nursing bras, training bras and even a plastic hard-shell bra called the SAF-T-BRA, meant to protect women working in factories. Training bras were a particularly striking development: before the 1950s, girls had worn loose-fitting camisoles until they grew into adult-sized bras. Now, with ever bigger breasts in vogue, going braless as a tween was considered unattractive and possibly a health risk. According to a 1952 article in Parents’ Magazine, girls who didn’t wear bras risked sagging breasts, poor circulation and difficulty nursing later in life. As women were pushed back into the home and into sexualized housewife roles after World War II, their bodies were also pushed in more directions and at a younger age than ever before.

The reaction to this unrealistic body image came with second wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s. Many women began wearing looser and more natural bras, like Rudi Gernreich’s No Bra, which debuted in 1964. More radical feminists abandoned their bras altogether, throwing them in “Freedom Trash Cans” along with high heels, cosmetics and other symbols of oppression. This is where the image of the bra-burning feminist originated, although almost no bras were actually burned.

While some women were rejecting bras altogether, others simply traded them out for more comfortable and personal options. In 1977, jogging enthusiasts Hinda Miller, Lisa Lindahl and Polly Palmer-Smith developed the early sports bra by sewing together two jockstraps. The garment gained popularity with the exercise movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Panties were also becoming smaller and more versatile; they shrunk from short pants in the 1950s, to briefs and bikinis in the 1960s, to hip-huggers in the 1970s and finally thongs in the 1980s. As the 1990s and third wave feminism broached the horizon, women found themselves with access to more undergarment choices than ever before, reflecting the breadth of choice they were fighting for in their day to day lives.

Modern underwear hasn’t changed structurally since the early 1990s. New and better materials are continually giving women more comfortable choices, but no really revolutionary new garments have developed. But as for the garments that we do have? We owe our boy shorts and bralettes to a century and a half of feminism.